THE RALUT SENIOR SCHOLARS

SYMPOSIUM

MASSEY COLLEGE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO

APRIL 7, 2009

Proceedings of

THE FOURTH ANNUAL RALUT

SENIOR SCHOLARS

SYMPOSIUM

Massey College

University of Toronto

April 7, 2009

Edited by Cornelia Baines

Toronto

Toronto Retired Academics and Librarians of the University of Toronto (RALUT) 2008

Contents

Introduction

The Presenters

Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: Is It 'Real' or Not?

Guile Becomes Women: Judah the Misogynist’s and Jacob ben Elazar’s Marriage Testaments

Evolving Attitudes to Democracy in Russia

Medical Care for the Aged

How Genes Work: The New RNA Surprise

The Bibliographical Imagination: How Humans Invented the Book

Panel Discussion

Introduction

RALUT is happy to present the proceedings of the Fourth Senior Scholars’ symposium, held this year at Massey College on April 9, 2009. In contrast to last year’s eight speakers, it was decided to have only six speakers in order to make time for a panel discussion moderated by Professor John Dirks. The panellists were Professors Michael Bliss and Peter Russell and they spoke on issues of crucial interest to Canadians. Interaction with the audience was encouraged.

The wine and cheese reception which characteristically ends the symposium was this year an occasion to mark the inauguration of the Seniors College, with those in attendance registering their willingness to be Fellows of the college. It was agreed to have a meeting later in the spring in order to appoint a College council.

RALUT must express thanks not only for the hospitality of Massey College and the welcoming address by Master John Fraser, but also to the speakers who prepared thoughtful and interesting papers, to the panellists, and the audience who gave their attention.

As then Chair of the Senior Scholars’ Committee and as ‘editor’ of these proceedings I am grateful to the organizing sub-committee (Professors John Dirks and Merrijoy Kelner) and to the speakers who so promptly submitted their manuscripts and so patiently answered my endless questions. Even more must I thank Ken Rea who single-handedly transmutes the edited manuscripts into the tidy package we call “The Proceedings”. He is truly amazing in his patience and his skills, a treasure for RALUT.

Presenters

Cornelia J. Baines, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto

Libby Garshowitz, Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations

Metta Spencer, Department of Sociology, University of Toronto

John T. Stevenson, Department of Philosophy, University of Toronto

Neil A. Straus, Department of Cell and Systems Biology, University of Toronto

Germaine Warkentin, Department of English, University of Toronto

Michael Bliss, Department of History, University of Toronto

Peter Russell, Department of Political Science, University of Toronto

Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: Is It 'Real' or Not?

Cornelia J. Baines

Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS) is also known as Environmental Sensitivity, Environmental Illness, 20th Century Disease and Sick Building Syndrome. It is a chronic, acquired disorder characterized by

• Recurring symptoms in many body systems that are triggered by chemically unrelated environmental substances;

• These exposures cause symptoms at very low levels that do not bother other people;

• And the symptoms increase in severity over time.

A typical medical history would involve a previously healthy middle-aged woman who begins to notice symptoms after an office renovation involving newly varnished floors, new partitions, re-painting, new carpeting or new furniture. On the weekends at home, the symptoms subside. On returning to the office the symptoms may not only recur but also they may get worse and worse.

The causes of MCS have been variously attributed to

• Immunological disorders although there is no compelling evidence for this;

• Psychogenic problems: again no compelling evidence;

• Particular mineral deficiencies within red blood cells: no compelling evidence;

• And vitamin deficiencies: no compelling evidence.

However, ‘neurological sensitization’ has been postulated and is plausible in that the sense of smell is heightened in MCS cases. Connections between the olfactory system and other parts of the brain might lead to the symptoms reported. In fact results from recent research using brain single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT scans) indicate this hypothesis may indeed be ultimately confirmed.

The rest of my paper will describe:

1. The background: how the research team with which I have been associated came about.

2. The foundation of our research: a self-administered questionnaire.

3. The case-control study which we then conducted.

4. And work in progress involving more questionnaire analysis.

The Background

In the early 90s, OHIP and the Province of Ontario under Mike Harris were faced with demands from the MCS community to pay exorbitantly high medical costs ensuing from patient visits to specialized MCS clinics in the US. Tens of thousands of dollars were being demanded for unvalidated diagnostic tests and treatment. The province decided to enlist the help of a widely recognized and admired epidemiologist, namely my colleague Professor Gail Eyssen. She then persuaded me to join her along with a clinician, Dr. Lynn Marshall, who herself has MCS. Epidemiology by the way is derived from the word epidemic and is defined as the study of the determinants and distribution of disease. Initially epidemiology focussed on infectious diseases. More recently it has focussed on chronic disease such as cardiovascular disease and cancer. Now epidemiologists are studying social problems such as alcoholism, violence and gambling.

The Questionnaire

After a literature review and discussions with focus groups including psychiatrists, toxicologists, occupational physicians, allergists, physicians specializing in MCS and MCS patients, we designed a questionnaire to allow documentation of many recognized features of MCS. 4,126 questionnaires were distributed to adults attending general, allergy, occupational and MCS practices with an expectation that there would be the smallest proportion of MCS patients in the general practice setting and the largest proportion in the MCS practices. The patients were asked if they experienced any one of 171 symptoms. If yes, they were also asked about 85 exposures and if these exposures had been linked to symptoms. There was a 62 percent response rate and we demonstrated that the questionnaire was reproducible and discriminantly valid (1, 2). "Reproducible" means that people gave similar answers to questions six months after their first response. "Discriminant validity" means that the questionnaire enabled identification of respondents likely or unlikely to have MCS according to the type of practice attended.

We found that women in the MCS practices compared to women in the general practices were:

• 12 times more likely to report feeling spacey;

• 12 times more likely to have a stronger sense of smell than others;

• 9 times more likely to feel dull;

• 8 times more likely to report difficulty concentrating;

• 7 times more likely to be tired, have a runny nose in the absence of a cold or to experience compulsive sleepiness;

• And 6 times more likely to have difficulty finding words, to feel clumsy or to be irritable.

10

Our attention was caught by the fact that many of these symptoms relate to brain function.

The Case-Control Study

To begin, it must be understood what a case-control study is. It certainly is not as you often can read in the Globe and Mail, a “case-controlled” study. Case-control studies are relatively quick and inexpensive compared to other epidemiological methods such as randomized controlled trials. By comparing patients already diagnosed with the disease of interest (cases) to people not known to have the disease (controls), a case-control study determines the extent to which each group was exposed in the past to the agent of interest.

For example: take 100 patients with lung cancer and another 100 people who do not have lung cancer. Inquiries about their past exposure to smoking can reveal that there is a strong association between smoking and lung cancer, that is, more cases were exposed in the past to smoking than controls. Such observations can be the basis for further research, both clinical and basic, to determine whether causation is involved as opposed to association.

However, be warned: case-control studies can yield very different answers to the same question depending on how they are designed.

From the questionnaire results we developed a case definition, an extremely important element of case-control methodology. This case definition allowed us to select from among the questionnaire respondents 223 cases and 194 well matched controls, all urban females aged 30-64 years.

Our design examined hypotheses about the underlying MCS biology that were current among MCS experts and other relevant specialists as revealed during the focus groups. However instead of an exposure like smoking, we looked at mineral levels inside red blood cells to examine whether in fact they were different comparing cases and controls as MCS experts believed. Other ‘exposures’ examined were haematological, biochemical and immunological markers, serum levels of volatile organic compounds and vitamin levels.

What did we find?

• White cell counts and total plasma homocysteine were lower in cases.

• Hemoglobin, one liver enzyme, and Vitamin B6 were higher in cases.

• Thyroid stimulating hormone, folate and Vitamin B12 did not differ comparing cases and controls.

• More cases than controls had detectable and higher levels of serum chloroform however all other volatile organic compounds with detectable levels were lower in cases.

• For nine minerals reported, chromium, copper, magnesium, manganese, mercury, molybdenum, selenium, sulphur and zinc, no significant differences were observed comparing cases and controls.

• However, comparing cases and controls, significant differences were found in genotype distributions for CYP2D6 and NAT2 and in particular the odds for being heterozygous for PON1-55 were significantly higher in cases. These genes are associated with detoxification processes and could potentially explain the biological mechanisms underlying MCS symptomatology. More detailed information is available in our published papers (3-5).

In short, while we did not find markers for MCS that were so strongly associated with MCS that they could be called diagnostic, we did find some biological differences between cases and controls that may lead to better understanding of MCS. In contrast, the gene-related findings were unequivocally important because they cannot be influenced by people’s exposures or their avoidance of exposures. These findings deserve further research.

Work in Progress

We are now analysing questionnaire results for 611 MCS and 1361 general practice female respondents age 30-45 years, in an effort to understand the inter-relationship and clustering of the many symptoms and exposures that were reported. It appears that MCS patients who report primarily brain-related symptoms (dull, spacy, difficulty concentrating and difficulty doing arithmetic) are those who report that food exposures cause them symptoms. Those who report primarily ‘allergic’ symptoms are those who report that inhaled exposures cause them symptoms. The same phenomena are reported by general practice patients but to a much lesser extent. It is clear that we still have much to learn about MCS.

In answer to the title’s question “Is MCS real or not?” I am persuaded that it is a real and debilitating syndrome causing major economic costs such as absenteeism from work, removal from the work force, special diets, possible social isolation and expensive renovations of existing homes. However the challenge is to make the diagnosis more reliable and to find the appropriate treatment. The US National Institutes of Health take the syndrome very seriously as does our government. The Canadian Human Rights Commission has a policy on MCS, to wit: “those with

environmental sensitivities are required by law to be accommodated”. Interestingly the Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s Programs devote a whole page to MCS to describe the condition and to request patrons to refrain from using any scented personal products when in Roy Thomson Hall.

References

1. McKeown-Eyssen GE, Sokoloff ER, Jazmaji et al. Reproducibility of the University of Toronto Self-Administered Questionnaire Used to Assess Environmental Sensitivity. American J Epidemiology 2000;151:1216-22.

2. McKeown-Eyssen GE, Baines CJ, Marshall LM et al. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: Discrimant Validity of Case Definitions. Archives Environmental Health 2001;56:406-12.

3. Baines CJ, McKeown-Eyssen GE, Riley N et al. Case-control study of multiple chemical sensitivity, comparing haematology, biochemistry, vitamins and serum volatile organic compound measures. Occupational Medicine 2004;54:408-418.

4. Baines CJ, McKeown-Eyssen GE, Riley N et al. University of Toronto Case-Control Study of Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: Intra-Erythrocytic Mineral Levels. Occupational Medicine 2007; 57: 137-40.

5. McKeown-Eyssen GE, Baines CJ, Cole DEC et al. Case-control study of genotypes in multiple chemical sensitivity: CYP2D6, NAT1, NAT2, PON1, PON2 and MTHFR. International. J. Epidemiology 2004;33:1-8.

Guile Becomes Women: Judah the Misogynist’s and Jacob ben Elazar’s Marriage Testaments

Libby Garshowitz

Introduction

I would like to take you back about 800 years, to the mid-13th century, to southern Spain, where Jewish poets, heirs to a rich literary tradition, are enjoying a wine-tasting soirée in a courtyard in Toledo. There, amidst flowers, trees, chirping birds, rapidly flowing fountains and lute-playing minstrels, these poets are reading and enacting their literary masterpieces, “maqamot”, written in rhymed prose and metered poetry. Patterned after Arabic literary traditions, the Hebrew maqama was more or less a fabricated adventure story as heroes, and heroines, traversing field and fountain, moor and mountain, proceed to recount their imaginary travels and adventures to a wide, attentive audience. The first adventure we’ll examine today was written by Judah Halevi Ibn Shabbetai (1168-1225), in a work entitled Judah the Misogynist’s Offering (Minhat Yehudah Sone Ha-nashim).

The hero, Zerah, is abjured from marriage by his wise, old father, Tahkemoni, who had been warned in a heavenly vision “to save Israel from women”. Why?

They are only after money and profit ...;

they’re responsible for all catastrophes

and wreak havoc upon humankind (1).

Drawing upon a long line of biblical female wrongdoers (for example, Eve, Rebecca, Rachel, Delilah), he advises Zerah to flee from treacherous women who seem outwardly serene but are internally wily. The price of marriage is death!

However, bachelorhood confers stature, majesty and success. It is better to encounter wild animals rather than enter women’s bedrooms which bode only destruction, tragedy and deceit, not joy. Tahkemoni considers

women (to be) men’s enemies...

they are good only for cooking, baking and

beautifying themselves...

And I have told you only a whit of their nastiness.

So Zerah and three companions withdraw to an isolated, Eden-like setting, reminiscent of magnificent Andalusian gardens and there they venture out to teach and preach celibacy as well as philosophy and Torah. Once a year however, Zerah leaves his idyllic retreat and enters the real world where he learns about what he has abandoned. There he is offered opinions quite different from what he had heard from his father. He is told about attractive, sought-after women who are beautiful, intelligent and ethical. These women are open to taking advice, discerning, capable of flowery rhetoric (mitbonenet mashal u-melitza) and skilled in writing poetry, playing the lyre and arousing both bliss and bathos. But these words were not spoken by Tahkemoni (he is already dead and buried) but by the wicked Kozbi bat Yaresha, a skilled sorceress and wife of the wizened and aged Sheqer. This shrew, guided by the despair of women, old and young, married and unmarried, who had no hope of bearing children, devised a plan that would counter the practice of celibacy promoted by Zerah and his companions.

To make a long story short, during the one month of the year that Zerah permits himself to come out of seclusion, he meets the beauteous Ayyala Sheluha, who possesses all the feminine qualities which Kozbi described. After a tortured inner struggle, Zerah is smitten, succumbs and a seven-day wedding feast takes place in which everyone participates. Unfortunately, Zerah is not sufficiently lucid when the “ketubba”, a Jewish marriage document in both Hebrew and Aramaic, is handed to him and in which another woman’s name has been substituted. The document details the dowry he must bestow on his beautiful bride. He must provide 100 foreskins for her virginity, as well as clean teeth, creaking knees and vertigo! He further promises plagues, troubles and sackcloth, while his intended bride in return promises him shame, destruction, scandal, burn for burn, wound for wound! Not a very promising start to a marriage!

On Zerah’s wedding night, Ayyala Sheluha is replaced by Marat Ritzpah bat Ayah, a black, ugly, hairy, repulsive hag, who, in the morning, makes more demands:

Gorgeous clothes for holidays and Sabbaths

Beautiful furniture and jewelry

Delicious food and intoxicating drink

Wet nurses for their children.

“Give me no wisdom or ethics!” says she. And her final orders to her husband are “go out, hunt, rob and steal!”

The hapless Zerah has indeed fallen into Kozbi’s elaborately-laid trap! The groom has become a laughing stock: “Where is the great preacher and teacher? Where is the wise counsellor?” He endures the ridicule of his three erstwhile friends who suddenly reappear, not to commiserate with him but rather to mock him. “A king has become a servant” as his degenerate wife has already informed him.

But all is not lost! Because he betrayed his own oath, Zerah is summoned to a court of law, where he faces Abraham Alfakhar, not only a poet and judge, skilled in both Arabic and Hebrew but also the patron of Judah Ibn Shabbetai, the author of the Misogynist’s Offering. He too is present, although masked. This trial takes place before no less a personage than King Alfonso VIII the Wise (1155-1214) whom Alfakhar serves as a courtier. Zerah strips away the mask to reveal none other than our author Judah Ibn Shabbetai (concealing and revealing being a common feature of maqama literature) who then protests that he loves his wife and children, and all that he has written is a joke!

A joke!! Much ink has been spilled by scholars over the centuries and even today about this joke. Is this tale a true exposure of our author’s misogynistic beliefs about women being filled with guile, deception and avarice? Or is this a parody or satire of marriage? Let us examine this story more closely. Misogynist literature was a common feature in medieval Europe (2). But as far as is known this is the only complete tale of its kind in Hebrew literature. Throughout this work, the author gives us signs and hints, (remazim) that this work must be read carefully. Even wise Tahkemoni’s diatribe against the follies of women and marriage was related to him in a vision (hazon) by a heavenly spirit (‘ofan). Furthermore, in his introduction, Judah Ibn Shabbetai informs his readers that he will subvert good to bad, wisdom to folly, truth to falsehood.

The key words used throughout this work are

• “sod” meaning secret or mystery

• “raz ve-satum” meaning completely unintelligible

• and “ve-ha-maskil yavin ve-yaskil”, meaning only the intellectually acute, razor-sharp wit will discern.

Furthermore, a close glance at the unusual ketubbah reveals that it was written on the 13th day of Adar, 4,977 in the Jewish calendar (1217 CE), marking the Feast of Esther and the eve of that rambunctious holiday, Purim. Purim is when all kinds of mischief and (mis)adventures described in the Book of Esther are permitted, mirroring the despair that turns to joy, the impending doom that turns to elation. As is customary in maqama literature and medieval Hebrew poetry, biblical verses, and even books, are suborned by writers for purposes of entertainment, pedagogy and morals—and sometimes for an opposite effect.

Therefore, Ibn Shabbetai’s Offering (minha) does not necessarily reveal his true feelings about women. Nor is it about misandry: the plotting women have both kind and unkind words to say about fortune-seeking scoundrels who abandon their marital and fatherly responsibilities. We can also discount misogamy, a hatred of marriage because Ibn Shabbetai himself, “the great impostor” when stripped of his mask, declared he loved his wife and children. Furthermore he says Zerah never existed nor did this episode ever happen. “It’s a game (mishaq)”, says Ibn Shabbetai!

And to illustrate his intertextual use of biblical books and verses, the books of Esther, Job and the most beautiful song of all, Song of Songs, are featured prominently throughout the story.

- Zerah (denoting "radiance") is the out-of-wedlock child of Judah and Tamar, (Genesis 37:12-30), born through trickery;

- the three friends who purportedly comfort Job, both comfort and deride Zerah;

- the name, Ayyala Sheluha, the raving, talented beauty, whose physical charms and talents are strongly reminiscent of the beauteous maidens in Song of Songs, signifies far more than beauty: she is "a doe let loose", a "writer of poetry";

- and to continue this theme of Judah Ibn Shabbetai's deception, the court hearing takes place, not in Toledo but in Shushan ha-bira, the capital city inhabited by Esther, Mordekhai, Haman and the Persian king.

Ibn Shabbetai's wicked use of biblical names, or variations of them, add to the fun of this maqama and also hint at what may transpire: Zerah's fair-weather friends are given names connoting goodness, most likely because they had envisioned Zerah's downfall in dreams and had warned him. On the other hand, the wicked shrew, Kozbi, denotes deceit and her shrivelled old mate Sheqer, denotes falsehood. Marat Ritzpa bat Ayah is introduced as "Marat, i.e., M(ist)R(es)S Ritzpah" but a secondary meaning of marat is "bitter, vengeful, black coal", illustrating Ibn Shabbetai's clever pun on this name.

Time does not permit an in depth analysis of this story, whether parody, satire or true misogyny. I would like, however, to suggest, as did Talya Fishman (3), that this story is more than a Purim Spiel. It is meant not only to entertain and offer fun, as is the intent of maqama literature, but also to teach morality, to state the obligations of husbands to wives (food, clothing and marital relations) (4), to retell the magnificence of God’s creation and to show the need for Jews to remain true to their faith. This may perhaps help us understand the mention of Zerah’s proselytizing (mityahadim) (5), for Ibn Shabbetai tells us that many people under Zerah’s tutelage had converted to Judaism. This is another ironic twist given what was already happening to many Jews in Spain, namely forced conversion to Christianity. Rather than just moralizing, Ibn Shabbetai chose to highlight what can happen to people should they choose folly over wisdom, or neglect the study and practice of Jewish values.

And this is what Jacob ben Elazar, (1170-1235), also resident in Toledo and also schooled in the Andalusian tradition of Arabic and Hebrew language and literature, sought to do in his work, Book of Parables (Sefer Meshalim) (6). In Maqama Nine, the tale of the aristocratic Sahar and the beautiful Kima, we have a different kind of love story, one in which our hero Sahar (moon) and heroine Kima (Pleiades) are permitted to declare their mutual infatuation with each other, “love at first sight” for both of them, but only from afar! Simultaneously smitten with each other’s beauty, and, more importantly, their poetic skills, and mad with physical lust and desire for each other, the two embark on a prolonged and courtly courtship which permits no touching, kissing or hugging, except from afar.

Kima, despite being hidden and protected in the royal palace, surrounded by a moat, high walls and a myriad of handmaidens, is a real coquette, a “tease”. She sends out “feelers”, words written on a fragrant apple, or on a curtain (parokhet), beckoning the hero with one hand, repelling him with the other. Such are the trials and tribulations of courtly love in medieval literature. Kima sends Sahar on futile journeys and then, with the help of her handmaidens, orders him back. The reader can’t help but be amused by the strong-willed and aggressive heroine Kima and the love-sick, angst-driven, frustrated Sahar who has to be constantly reminded by the chaste (in deed, if not in words) Kima that they must keep their distance. Such is the fate of those in high society. It is commoners whose passions are unbridled and uninhibited.

It is the author, Jacob ben Elazar, who has allowed Kima to be the more astute, take-charge person in this courtship. It is Kima who reminds the distraught and anguished Sahar that true love is pure, a meeting of hearts, souls and minds, not flesh. And it is Kima who argues that they must remain celibate. Furthermore, it is through Kima that Jacob ben Elazar preaches and teaches the virtues of abstinence before marriage. It is Kima who speaks of “rules and precepts” that one must observe in courting. It is the task of the aristocracy to embrace moral instruction, righteousness, justice and fairness just as Tahkemoni, Zerah and his three friends had taught: “receiving instruction in wise dealing, righteousness, justice and equity”.

Eventually, Sahar is allowed to enter the palace, they marry, have an elaborate one-year wedding feast and upon the violent death of Kima’s tyrannical father, the king, Sahar becomes ruler. And guess what happens in their marriage? They begin a cycle of quarreling and making up! The eloquent, intellectually superior Kima has become a garrulous, nagging shrew. All this to prevent their love and lovemaking from becoming routine! It is Sahar who solemnly declares: “Both desire and war kill! Woe to warriors and woe to lovers!” Both Sahar and Zerah share the experience that

...a beloved speaks no truth,

love lacks understanding and knowledge

and is unable to distinguish between good or bad.

Such is the lesson the lover takes to the grave.

What both heroes have in common is their status as 'love-slaves'. Both have been entrapped: Zerah by women who were denied marriage and the benefits of marriage (food, clothing and marital relations) and Sahar by a woman who wanted to keep the marriage rite sacred.

In Judah Ibn Shabbetai’s Offering and Jacob ben Elazar’s Sahar and Kima’s Love Story, both authors have set out to amuse their listeners, the former by parodying marriage, the latter the idea of courtly love because Judaism, for the most part, frowned on an ascetic life. Besides reinforcing Jewish values, both authors have used the language of love, allure, seduction and even trickery to moralize, more or less subtly, and above all — to entertain their listeners.

References

1. See “MinhatYehudah, Sone Ha-nashim” in Eliezer Aschkenasi, Ta’am Zekenim (Frankfurt am Main, 1854), 1-12 ; Raymond P. Scheindlin, “The Misogynist,” by Judah Ibn Shabbetai, in Rabbinic Fantasies, eds. David Stern and Mark Jay Mirsky (Philadelphia and New York: The Jewish Publication Society, 1990), 269-293.

2. For example, Chaucer’s Wife of Bath, Boccacio’s Decameron.

3. "A Medieval Parody of Misogyny: Judah ibn Shabbetai’s Minhat Yehuda sone hanashim", Prooftexts 8 (1988): 89-111.

4. Exodus 21:10 (she’erah, her food, kesutah, her clothing, ve-‘onatah, and her marital relations, lo yigra, shall not diminish).

5. Esther 8:17

6. Sefer ha-meshalim, Book of Tales (or, Sippurei Ahava, Love Stories), ed. Yonah David (Tel Aviv, 1992).

Evolving Attitudes to Democracy in Russia

Metta Spencer

Question: How can repressive societies best acquire peace and democracy? My answer: through engagement in transnational civil society organizations that address global controversies. One case study — Russia — will reveal the consequential nature of such “bridging” networks on state policies.

Mary Kaldor defines civil society as “the realm not just between the state and the family but occupying the space outside the market, state, and family — in other words, the realm of culture, ideology, and political debate”(1). Civil society comprises clubs, academia, NGOs, trade unions, churches, consumer organizations, foundations, charities, and more. Participation in such self-forming groups confers the skills of democratic citizenship.

Russians pin their hopes for democracy on the growth of these independent organizations. And their rulers, fearing such organizations, are deliberately impeding civil society. A key aspect of civil society is its voluntary, non-coercive nature. By definition, civil society excludes governmental officials. As we shall see, this definition was too restrictive during the gestation of perestroika, when the most creative civil society actually existed secretly inside state bureaucracies.

Yet not all civil society organizations have equal democratizing effects. The sociologist Robert Putnam (2) has suggested that civil society organizations can have two different, even contradictory, effects — either “bonding” or “bridging” their members. Organizations whose members are socially similar develop “bonds,” intensifying internal solidarity, whereas those with diversity of membership tend to “bridge” the society’s disparate elements. I want to show here that these bridging groups effect most of the democratizing influences.

Their political diversity makes “bridging” civil society organizations facilitate democracy by destroying the illusion of unanimity — an illusion that a dictator uses for controlling society. The solidarity within a “bonding” organization dampens internal dissent, whereas a transnational group, with its diversity, inevitably “bridges” differing members, as I have learned when meeting Russians over the past 27 years.

I began visiting the Soviet Union in 1982, participating in an “East-West Dialogue” about nuclear arms. Soon I discovered that two distinct, polarized civil societies existed in Russia, both sharing the same ideals: democracy, peace, and human rights. However, both were “bonding” groups, each one internally loyal but lacking “bridging” connections to the other. In fact, each of these two communities was hostile to the other. Nevertheless, they both had friendly “bridging” relationships to foreign peace activists, of whom I was one.

One controversy divided them: whether the Soviet Union would be changed “from the top down” (by government officials) or “from bottom up” (by grass-roots anti-state movements). Almost all reformers who believed that change could only arrive “top down” belonged to the Communist Party. By definition, members of the state could not be considered part of civil society, but in reality they functioned exactly as such. As a semi-secret society, they constituted a civil society within the Soviet state that they sought to liberalize. Tragically, these two remarkable civil societies refused to cooperate with each other. Their polarization defeated the Gorbachev reforms. Both sides failed to recognize, until too late, that the reforms they sought would arrive both “top down,” and “bottom up” — and even “sideways” from transnational “bridging” civil society.

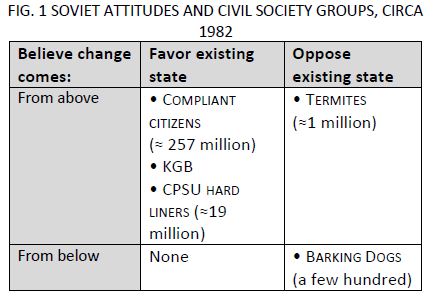

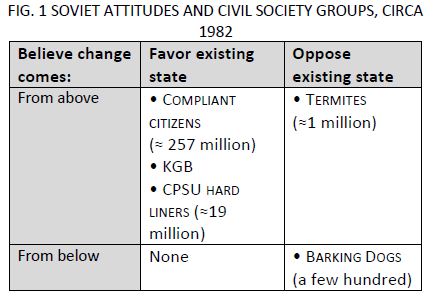

Historians have yet to reveal the impact of East-West dialogues on official Russian policies. Here I’ll present typologies of Russian opinions at three phases — around 1982, 1991, and 2009 — concerning their prospects for peace and democracy.

Long ago I lost count of my trips to Russia, which usually occurred once or twice a year. By 1998 I had interviewed over 200 people, many of them repeatedly and about half of them Eastern and half Western. The list still grows, with 35 interviews in Ukraine and Russia in 2008 and continuing discussions by phone.

Russia in 1982

In 1982 nuclear disarmament was the issue. Initially I was a guest of the state organization, the Soviet Peace Committee, but my real counterparts were the independent Russian activists who were excluded from those dialogues and assaulted or jailed for such moderate activities as organizing exhibits of peace art. Thus I met both categories of reformers:

BARKING DOGS

Independent Russian activists wielded no political power but considered themselves morally bound to speak honestly. Not all of them liked to be called “dissidents,” so I called them BARKING DOGS. They could not “bite” but they did alert the public to political dangers. I always visited some BARKING DOGS when in Moscow, until finally I was expelled temporarily for doing so. Most of them also were deported before perestroika got underway, but other independent activists have continued to emerge. I have always admired these courageous, honorable people.

TERMITES

My expulsion in 1986 demonstrated the animosity of only a few KGB functionaries. High-level policymakers, by contrast, were remarkably friendly interlocutors in the dialogues. As a proponent of nuclear disarmament, I was accustomed to being disregarded by officials in the West, but in Moscow several top officials showed me surprising respect, especially when I tactfully suggested that Western politicians were unlikely to favor military disengagement so long as dissidents were mistreated in Russia.

“On-stage” in the dialogues these Soviet officials gave canned speeches, but during coffee breaks they urged me to keep raising the same points. I was astonished; these people were trying to change their policies from within, and they saw us Western peaceniks as their allies! Nobody had told me to expect such private conversations. I learned that there had long existed numerous reformists — possibly one million — within the Party. They shared my values and were, “burrowing from within,” while waiting for a chance to apply their deviant liberal ideas. I called them TERMITES.

Within a couple of years they would be helping Gorbachev to create perestroika.

Some fortunate TERMITES could travel abroad, participating in transnational civil society organizations such as Pugwash, the Dartmouth Group, the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, and European Nuclear Disarmament (END). Alliances emerged between Western scientists (even those working on nuclear weapons) and Russians. Westerners say that they could observe the opinions of their Russian friends changing (3). Thus Joseph Rotblat told me,

Initially, I think, the Pugwash exercise was largely a process of education of the Soviet and American scientists. We met in this room - people who were very much involved in the Manhattan project. I remember the first night we sat here and discussed all these issues. It was eye-opening with the Russians. Sometimes one could see this education, as in the case of the ABM. At other times, we could not see it for a long period, but then subsequently we could see the effects. So I believe we really played quite a part. I don't want to be immodest, but on the other hand I don't think we should be too modest. We know from subsequent discussions with people - Georgi Arbatov, for example - that our gradual discussions in Pugwash with people who were in high positions in the hierarchy influenced Andropov, to begin with. He was a perceptive man, unlike Brezhnev or Chernenko. He could listen. And of course Gorbachev was his protegé (4).

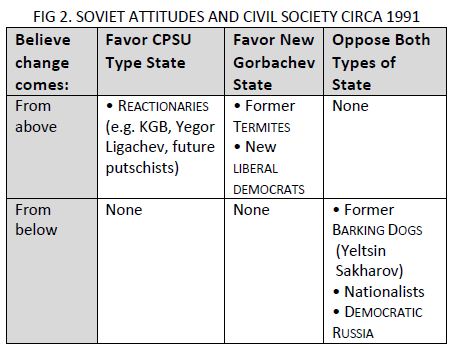

The following typology depicts Soviet political attitudes shortly before Gorbachev's elevation. I consider the TERMITES and BARKING DOGS as civil society organizations, but not the rest. Indeed, the near-absence of civil society is a defining trait of authoritarian states.

The grassroots, risk-taking dissidents (BARKING DOGS) and the progressive-minded but circumspect party officials (TERMITES) both hated the Soviet state, so they should have been allies. But instead they were bitter enemies. The TERMITES expected change only from above but the BARKING DOGS expected democracy, peace, and human rights to arise only after ordinary citizens began speaking out. Numbering only a few hundred, they paid willingly for their frankness and felt contempt toward TERMITES. One dissident interviewee called such conformists “whores.”

Later we would witness this mutual antagonism in the public wrangling between Gorbachev the former TERMITE and Sakharov the former BARKING DOG. However, both groups accepted us foreign peaceniks.

I was documenting the influences of TERMITES’ conversations with Westerners (and with Eurocommunists in such places as Prague) on Soviet policies (5). After Gorbachev invited "new thinking," suggestions were funnelled to him through such TERMITES as Georgi Arbatov, Fyodor Burlatsky, Yevgeny Chazov, Yevgeny Primakov, Vladimir Petrovsky, Roald Sagdeev, Georgy Shakhnazarov, Yevgeny Velikhov, and Alexander Yakovlev. Their proposals ended the Cold War and launched democracy.

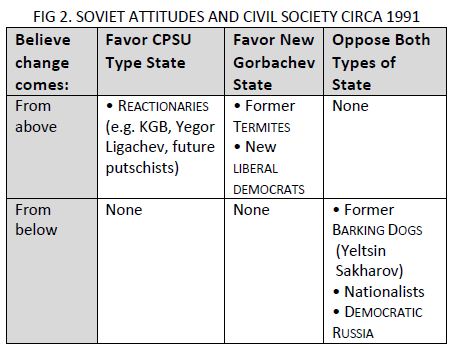

Russia in the 1990s

Gorbachev knew that his elevation gave him a unique opportunity to change society. As a centrist, he hoped to move a unified country toward peace and democracy.

However, the transition brought unexpected difficulties. He encouraged civil society and mass movements, but many Soviet citizens equated democracy with “national self-determination” and became separatists. Moreover, economic reforms were slow and some people actually experienced hunger. During one visit I saw thousands of Muscovites selling their personal belongings beside the street, while the food shops offered only butter and jars of pickles. Understandably, hostility arose toward Gorbachev. He made it safe for citizens to grumble publicly, and millions of them did so. Almost all these new BARKING DOGS became followers of the impulsive Boris Yeltsin, who claimed to be more democratic than Gorbachev. They also followed Andrei Sakharov, whom Gorbachev had released from house arrest but who maintained the habitual BARKING DOG hostility, especially toward such former TERMITES as Gorbachev himself.

Opinions polarized. Some freely-elected politicians (e.g. Yegor Ligachev) preferred old Communist ways, while the democrats demanded radical changes and renunciation of the CPSU. Gorbachev, now lacking a centrist base, began alternating between right and left, alienating even his allies.

Public opinion remained divided over whether to support the state, but now the question was: which state — the old CPSU-led state or Gorbachev’s new centrist one?

“Democrats” opposed both. A popular movement, “Democratic Russia,” took to the streets, intending to sweep away both Gorbachev and the CPSU, thus inviting the democracy that they supposed would emerge automatically. Figure 2 shows the political opinions before the coup.

First the reactionary coup plotters tried, and failed, to oust Gorbachev. Then Yeltsin, the leader of the new “BARKING DOGS,” tried and succeeded. All my Russian friends applauded the break-up of the Soviet Union. Almost no Western liberals did so.

Democracy did not come automatically. Instead, Yeltsin’s rule was chaotic and corrupt. He shelled the parliament, killing hundreds of his political opponents, then created a new constitution giving himself almost unlimited powers. He privatized industry and turned the big enterprises over to oligarchies that manipulated Russia’s new political parties and controlled the media.

Eight years later, Yeltsin resigned, apologizing and bequeathing the state to his protégé, Vladimir Putin, who curtailed most democratic reforms and crushed the Chechen rebellion. Boosted by high oil and gas prices, Russia’s economy improved. Putin’s popularity soared. Now any affluent Russian could travel abroad, and many people vacationed in Europe. It was no longer a rare privilege for a Russian to attend a Pugwash conference, so transnational civil society organizations declined. However, a seaside resort presents few occasions for serious conversation with foreigners. A drift began toward a “new Cold War,” mainly because of George W. Bush’s policies, but also because of declining Russian engagement in international civil society.

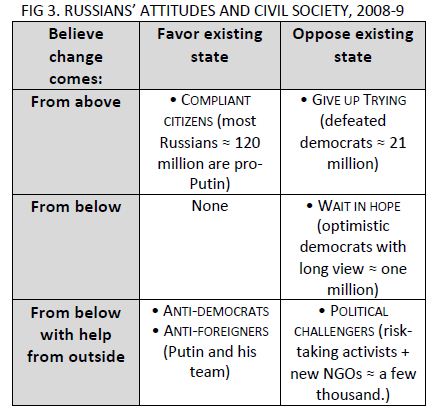

Russia in 2008

I arrived back in Moscow on the day after President Medvedev’s 2008 inauguration. Oddly, I sensed more wariness toward me than in the early 1980s, when Soviet TERMITES and BARKING DOGS had considered me an instant ally. The current dissidents did not fit into either previous typology. All POLITICAL CHALLENGERS still agreed that political reforms come from below — but now only with considerable foreign support. And no longer were any TERMITES working furtively for reforms within the state. The polarization was still between those who did and did not like the existing state. Vladimir Putin shared power with President Medvedev, who could enact laws by decree. Still, this was not totalitarianism. People were not afraid to speak their minds in restaurants, taxicabs, or the Internet. But nobody pretended that it was democracy.

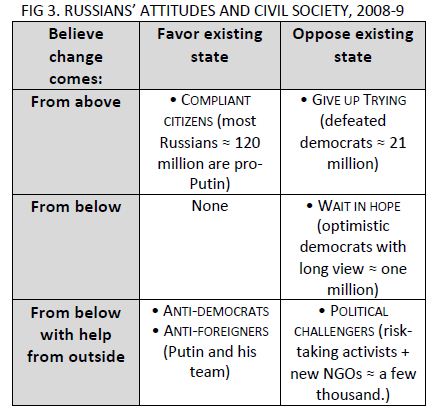

Many Russians no longer wanted democracy anyway. Yeltsin had given it a bad name. Many Russians wanted only order and prosperity, which Putin had restored. People knew that the new economic growth was not really of Putin’s making, but resulted from the soaring price of oil (6). Nevertheless, that bonanza made him popular. Here is the new typology of Russian attitudes, circa 2008.

COMPLIANT CITIZENS

Most people belonged in top left cell. According to a poll in July 2007, 85 percent of Russia’s citizens approved of Putin (7). Thus about 120 of the 142 million Russians were “compliant” pro-Putins. Many of them now belonged to civil society organizations without supposing that this would foster democracy.

ANTI-DEMOCRATS AND ANTI-FOREIGNERS

The left column (those who accepted the Putin/Medvedev regime) included two other logical possibilities — those believing that democratic change comes from below and those believing that it would also require a “sideward” push from outside.

Putin and his entourage belonged there, anticipating a foreign-sponsored colour revolution similar to the Orange Revolution in the Ukraine. To prevent this, Putin regulated NGOs so severely that they could barely function. Shaken by “people power” in the “near abroad,” Putin had made it illegal for Russian civil society organizations to accept foreign funds for political activities.

POLITICAL CHALLENGERS

Now consider the right column: the opponents of the existing state. We find three categories, none matching the old TERMITES or the BARKING DOGS. In the bottom-right are POLITICAL CHALLENGERS who, unlike earlier BARKING DOGS, believe they need “sideways” help from outside. Almost all of them found legal loopholes to accept foreign funds. Sergei Kovalev, one of the few original BARKING DOGS still active in Russia, recalled in our 2008 interview the impact of outside supporters during the 1980s:

Dissidents here could be eliminated very easily. ... But dissidents had one last tool that turned out to be the best one because it was the appeal towards popular opinion in the West. And in the West, popular opinion stimulated their leaders. Yes, the 'sideward' pressure turned out to be the most important one (8).

Among the POLITICAL CHALLENGERS was the chess champion Garry Kasparov, who headed a disparate coalition of parties, "The Other Russia," which had tried to compete in the 2007 elections but were assaulted and arrested. Kasparov admitted that he fears for his safety, saying, "They watch everything I do in Moscow, or when I travel.... I don't eat or drink at places I'm not familiar with. I avoid flying with Aeroflot."

Another old-style BARKING DOG is Lev Ponomarev, who leads Russia’s human rights movement. Weeks before we met, TV viewers had witnessed the police beating him in the street. He still works tirelessly, protecting prisoners from torture and teaching youths what their legal rights are if they are arrested for wearing Mohawk haircuts or nose rings.

GIVE UP and WAIT IN HOPE

These are two categories comprising most opponents of Putin’s government. These people wanted democracy but did not work against the regime. They had compelling grounds for caution, for to challenge is to court trouble. Polls estimate that 85 percent of the 140 million Russian citizens favored Putin’s government. Thus 22 million people did not (9) but of these probably 21 million were unengaged.

Most Russians whom I met in 2008 were GIVE UP types. One example was K, who had been a municipal politician during the Gorbachev years. During the August coup, he had gone from tank to tank outside the White House, imploring the soldiers to refuse orders to attack. Later K had criticized Yeltsin for shelling parliament. For this he lost his political career. Now he viewed the future with resignation.

WAIT IN HOPE

Finally, I turn to WAIT IN HOPE — the group that fascinated me most. Like the GIVE UP people, they did not expect democracy soon but, unlike them, they were optimistic that eventually it will come. Within fifteen years, they said, the Russian people will be “ready” for democracy. This is because civil society is developing and enhancing Russians’ capacity to manage their collective affairs.

The most remarkable of these WAIT IN HOPE interviewees is the former dissident Ludmilla Alexeeva. I was puzzled by her optimism but she explained:

With such a history as ours, we have a pretty good proportion of normal people, brave people. It should be much less. We decided to reach democracy. It's a heroic decision and we will be a democratic country but we cannot do it so quickly. We cannot! Be more patient! . . .

In fifteen years, I believe we will reach democracy. Because what does democracy mean? When people won’t permit their rulers to abuse their power! We should arrive at such a society but it’s impossible to make it quickly. I would say we’ve come quite a distance since the end of the eighties....

In the Soviet Union, people couldn’t do anything for themselves. Either the state did something for the people or it wasn’t done at all. For example, I would like to have a good apartment. If the state didn’t give it to me, I could not have it. It was impossible. We lived in such a way for three generations. And when the Soviet Union was crushed, we were like kids. We didn’t know how to do anything. We had to learn to be grown-up people in a very cruel way because the state forgot about us. The state crushed our economy and our social system, and nobody helped people in this country. Those who couldn’t learn to do things by themselves, those who couldn’t pass the transition, they just died. …. People who are alive now are mature people. It’s a different people from the Soviet Union.

I can see that all the stages that took dozens of years or centuries in Europe and America, we are passing through in a few years. Now we have turned from bandit capitalism to state capitalism. Of course it’s not democracy. But we will pass to other stages too—quickly. Believe me. Because in parallel with this political development, we have the development of civil society (10).

Alexeeva is honored as a founder of the Moscow Helsinki Group and to this day can phone Putin and tell him what he should do. He does not follow her suggestions, but because of her high moral status he must listen to her politely. She invites his political opponents to her apartment for tea and urges them to cooperate among themselves, but she is no longer a dissident. The country has a constitution now and she is merely upholding it, she explained. It is the people in government who are “dissidents” by violating the constitution. Some old allies, such as Ponomarev and Kovalev, are still POLITICAL CHALLENGERS but Alexeeva waits optimistically.

I was struck by this hopefulness. What oracle was Alexeeva consulting that gave such upbeat predictions? The transition to democracy is not automatic. Alexeeva defined democracy as “when people won’t permit their rulers to abuse their power!” But why did she expect people would be able to withhold permission?

Freedom is that space beyond the range of guns, whips, and locks. Russians, more than anyone, should recognize totalitarianism as an objective “social trap” from which escape may be impossible, no matter how “ready” victims are in their psychological development. “Waiting in hope” is no defence against authoritarianism.

Instead of Waiting in Hope

A dictator’s power comes from inducing others to enforce his orders. He requires an illusion of unanimity — which arises too easily in “bonded” organizations. BARKING DOGS and POLITICAL CHALLENGERS always are a small minority. Most people in a group censor themselves. A would-be dictator exploits this tendency to produce the illusion that everyone believes in him.

Psychologists know the power of conformity (11). The tendency to conform occurs in groups as small as three. However, if even one person tells the truth, others will speak honestly too. The real defender of democracy is the person who speaks truthfully first, breaking the illusion of unanimity. If each citizen believes himself unique in doubting the dictator, he will not resist. This sheep-like compliance reflects an objective predicament, a “social trap.” “Waiting in hope” cannot prevent this. The only way to keep social traps from closing is vigilant truthfulness.

The WAIT IN HOPE Russians are partly right: The path to democracy runs through civil society. Yet not every civil society organization liberates, but only those fostering diversity. If many citizens belong to transnational civil society organizations (e.g. Pugwash, International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, or Green Cross International — the environment-and-peace group that Gorbachev founded) they will hear a diversity of opinions. No illusion of unanimity arises. Hence transnational civil society is of utmost importance for democratization and peace. When people become “ready” in other ways, bridging organizations help them to recognize and oust illegitimate rulers.

The Future

In the end, no BARKING DOGS, POLITICAL CHALLENGERS, nor even TERMITES managed to establish democracy. The courageous Soviet dissidents were assaulted, imprisoned, and expelled from the country. It was the TERMITES— or rather one particular TERMITE, Gorbachev himself — who offered democracy. Citizens recognized neither the value nor the fragility of what he offered, but preferred Yeltsin’s coup. Most Russians still believe that they had experienced democracy under Yeltsin and had found it unsatisfactory.

Civil society is increasingly restricted. Since December 2008 a Russian citizen may be charged with high treason and imprisoned for 12-20 years for telling foreigners state secrets or helping them “perform activities detrimental to the security of the Russian state” (12). They will be tried by three judges, not a jury of peers. The law implies that any information given to a foreigner should be approved in advance by “competent authorities.” This law is a social trap, waiting for its victims.

Sideways Assistance

Ukraine’s Orange Revolution exacerbated Russian public opposition to democracy. Putin blamed it on Western governments and foundations, who, he believed, had sponsored the “regime change.” Not only Russians but also many Western liberals now question the legitimacy of promoting democracy, which had been a bipartisan doctrine until Bush invoked it to justify attacking Iraq (13). Millions turned against it (14) and now it is politically fraught to offer other countries assistance in their pursuit of democratic governance.

Yes, Western democracies did support the colour revolutions, but most of the funding for them was indigenous. These “revolutions” were home grown manifestations of public outrage against election fraud and/or repressive governance. No grassroots democratic movement can ever be run from Washington. “Sideways” support can help democratic movements, but the impetus invariably springs “from below.”

“Top-down” reforms have even worse results. If the public does not want democracy but it is given to them from above (as Gorbachev did) they probably will not keep it. Freedom House monitored 67 democratic transitions over a 33-year period. In 48 percent of them, nonviolent popular fronts were engaged. Five years later, those led “from below” were far more likely to still be democratic than were “top-down” transitions led by elites (15).

As POLITICAL CHALLENGERS now realize, democracy must arise from below, but “sideways” support also is necessary in three ways.

First, other states can uphold international standards that POLITICAL CHALLENGERS can invoke. For example, Russia was set to host the G-8 summit in St. Petersburg in 2006, but other countries criticized a proposed Russian law curbing pro-democracy NGOs. Putin deleted its worst elements (16).

Second, Russia’s civil society organizations should be assisted financially — not political parties, but pro-democracy movements, independent media, civil society development, public debates, election monitoring, and exit polling. According to existing international legal principles, NGOs have the right to obtain funds from all legal sources.

Third, “sideways” support for democratization involves conversations. Even “bonding” groups develop skills, but “bridging” groups do more: Breaking the illusion of unanimity, they empower members to resist authoritarian rule.

The ideas that liberated Russia from communism were mainly imported by TERMITES in transnational civil society organizations. Today transnational civil society needs to be re-invigorated and expanded, for the sake of peace and democracy.

References

1. Mary Kaldor, “The Idea of Global Civil Society.” International Affairs 79, 3 (2003), p. 584.

2. Robert D. Putnam, Robert Leonardi, Raffaella Y. Nanetti, Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1994.

3. Bernard Lown, Prescription for Survival: A Doctor's Journey to End Nuclear Madness. Berrett-Koehler, 2008.

4. Metta Spencer (Interviewer) “The Impact of Pugwash,“ Peace Magazine, Jan-Feb. 1996, p. 24. http://archive.peacemagazine.org/v12n1p24.htm

5. Metta Spencer, “'Political' Scientists,” The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 51, No. 4, July/Aug 1995, pp. 62-68. metta.spencer.name/?Papers:Academic_papers&id=14

6. Michael McFaul and Kathryn Stoner-Weiss, “The Myth of the Authoritarian Model: How Putin’s Crackdown Holds Russia Back.” Foreign Affairs, Jan/Feb. 2008.

7. www.Levada-center.ru, April 2007.

8. Sergei Kovalev, Interview with Metta Spencer, Moscow, June 2008.

9. In authoritarian countries, one questions the accuracy of responses to polls. However, these surveys are consistent with other evidence that seem to validate the results.

10. Ludmilla Alexeeva interview with Metta Spencer. Moscow, May 26, 2008.

11. Solomon Asch, “Opinions and social pressure.” Scientific American, 1955,193, 31-35.

12. Putin introduced this amendment to Article 275 of the Russian Federation Criminal Code.

13. Peter Baker, “Pushing Democracy: Quieter Approach to Spreading Democracy Abroad.” The New York Times, Feb. 21, 2009.

14. James Traub, The Freedom Agenda: Why America Must Spread Democracy (Just Not the Way George Bush Did). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008.

15. Adrian Karatnycky and Peter Ackermann, “How Freedom is Won: From Civic Resistance to Durable Democracy,” www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=138&report= 29

16. Carl Gershman and Michael Allen, “The Assault on Democracy Assistance.” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 12, No. 2, April 2006, p 48.

Medical Care for the Aged

John T. Stevenson

Introduction

In late 2007 Mr. Samuel Golubchuk lay in the intensive care unit of the Salvation Army Grace Hospital in Winnipeg. The attending physicians decided that he should be removed from the ventilator and other life support systems to which he was attached. After all, he was 84 years old, and had been hospitalized for several years after a fall causing severe brain damage in 2003. He had part of his temporal lobe removed in 2005, and had been admitted to the Grace ICU suffering from pneumonia and pulmonary hypertension. The doctors and nurses maintained that, although there were some brain stem functions intact, he was unconscious and unresponsive to stimuli. Moreover, he was using up valuable and scarce medical resources with no hope of recovery.

Mr. Golubchuk’s son and daughter strongly objected. They claimed that he was not brain dead and that according to their Orthodox Jewish religious beliefs every effort had to be made to keep him alive. To fail to do so was tantamount to assault. They obtained, on an emergency basis, an injunction against the Grace and three doctors preventing them from stopping Mr. Golubchuk’s life support. Some doctors resigned in protest and the case became a cause célèbre. On February 13, 2008 Mr. Justice Schulman of the Court of Queen’s Bench of Manitoba extended the injunction until the full case of alleged assault could be heard (1). I shall return to the Golubchuk case in my conclusion.

Concern over the utilization of scarce resources has led some medical ethicists to propose a radical solution. In 2000 John Hardwig, of the prestigious Hastings Institute in the US, published a book entitled Is There a Duty to Die? in which he claimed that there is such a duty. A number of other ethicists have similarly argued that old people in particular have a real and compelling duty to die when there is a scarcity of resources. In that case, the young should be favoured over the old (2, 3, 4).

There you have the two extremes: unlimited medical care for the aged versus none for them. The moral issue is: What restrictions, if any, should there be on medical care for the aged?

My position is as follows. I am opposed to strictly age-based rationing of medical resources, but I am in favour of the circumstance and condition appropriate allocation of medical resources. By “circumstance” I mean the fiscal and medical resources available at a given time. By “condition” I mean the medical condition of a given patient. I have used the word “allocation” rather than “rationing,” because rationing connotes a severe shortage and whether in Canada there are, in general, severe shortages of medical and financial resources is a point at issue.

Justice, rights and duties are predicated on feasibility. You have no duty to do the impossible, nor have you any right to demand it. What is possible in the circumstances of one country at a given time might not be possible in another. I shall restrict my discussion to Canada’s situation and whether we are faced with general scarcity of resources.

So before turning to moral issues—such as questions of intergenerational justice and benefits/disbenefits—we must examine the possibility, the economic feasibility, of our providing medical care for the aged. To do so we will examine the nexus of demographic changes, changes in patterns of morbidity, rising costs to the provinces, the division of constitutional responsibilities, a brief look at some age-appropriate potential cost savings, and some international comparisons of health expenditures (5, 6, 7).

Feasibility of Providing Medical Care for the Aged

An important issue is the age distribution of Canada’s population and its effect on health costs. Our population pyramid looks like a python that has swallowed a pig, with the pig gradually moving north. The pig is, of course, the boomer generation. In 1921 less than 5% of our population was over 65; in 1991 that proportion had risen to over 10%; by 2041 it is estimated that it will rise to over 20%. Noteworthy is the substantial increases expected by 2041 in those in the 75-84 age group (~7%) and those over 85 (~3%).

What effect will this have on medical expenditures? It is true that they will probably increase with our aging population, in particular the big increase in those in the age groups 75-84 and 85+. In 1996-1997 the hospitalization rate for people age 45-64 was 10,000/100,000. For those over 75 the rate was well over 50,000/100,000 for men and somewhat less than 40,000 for women. In 2005 the average cost of health care in Ontario for those between 15 and 45 was $1,280 per year, whereas the cost for those over 65 was $7,723 per year. But what is also happening is that some acute, life-threatening disorders have turned into chronic but manageable conditions. This is true, for example, with heart disease: the death rate of 2,000/100,000 in 1980 fell to about 1,300 in 1996.

There is concern in many quarters that as the boomers age, general longevity increases and the costs of medical care rise, we will find an unsustainable proportion of GDP being devoted to medical care. What is scary is the proportion of provincial budgets devoted to health, a proportion so large and growing larger that it threatens all other provincial responsibilities, such as education, welfare and infrastructure. In 2005 Ontario Finance Minister Sobara pointed out that 45% of spending on provincial programs was devoted to health care. Because medical costs were increasing by 6% per year, more than expected increases in GDP, medical expenses would eat up 55% of the budget by 2024. In fact, in fiscal 2008-2009 49% of the provincial budget went to health. Certainly health costs are straining our provincial resources.

Unfortunately, Canada in the 21st century is stuck with an outmoded 19th century constitution that is practically impossible to change. The Fathers of Confederation did not envision making massive expenditures on higher education, pensions and health care. We have had to jury-rig solutions, such as transfer payments to the provinces, to solve some of our provincial fiscal problems. We could do more to rebalance the division of responsibilities and taxation powers—perhaps through a greater transfer of tax points from federal to provincial coffers.

It is worth remembering, too, that the working population was able to support the boomers when they were expensive youngsters and another working population can similarly support them when they are aged, especially given the fact that the boomers contributed to a larger GDP.

We also need to restrain rising costs. We already know many of the things that can be done to contain costs and improve medical services. I shall mention here only three that are especially important in caring for the aged who have incurable but manageable conditions or who are in the last stage of life.

First, our hospitals are more crowded and expensive than they need to be in significant part because of the large number of elderly who are housed there simply because there is nowhere else to put them. We need more and better home care programs so that the elderly can “age in place,” and we need more and better nursing homes that are more appropriate and less expensive than hospitals.

Second, we need to obviate the need to ambulance sick nursing home patients to expensive hospital emergency wards, where they often linger for many hours lying on gurneys in corridors. Toronto Western Hospital has started a Long Term Care Mobile Emergency Program for bringing services to downtown nursing homes that has reduced emergency-room visits from them by 77%. We need more such innovation.

Third, surveys show that most Canadians would prefer to die at home, but some 80% end up dying in hospitals. A far better and relatively inexpensive alternative to hospitals, and one that offers compassionate and appropriate care to those in the last stage of life, is a hospice, whether home- or residence-based.

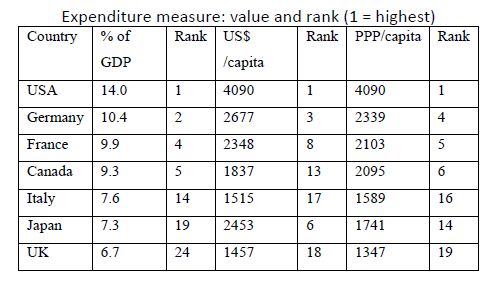

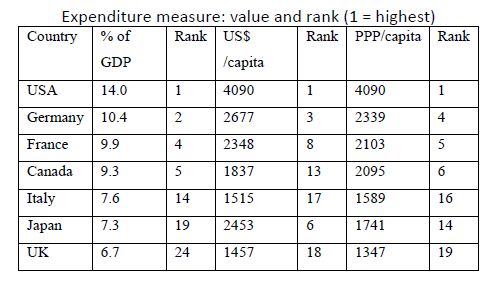

Finally, it is salutary to compare Canadian health costs as a whole with international data. We then see that our health costs are not so overwhelming, whether measured in terms of percent of GDP, US$ per capita, or PPP (Purchasing Power Parity.)

The figures in the table support the conclusion:

...Canada's current health expenditures do not support panicky calls for radical calls in Canada's medicare system...[for] international data suggest that Canadian spending falls within the general levels found for other countries at its level of development (8).

One reason for rationing medical care for the aged would be lack of resources to do so. But in Canada's case we have seen good grounds to believe that we can afford to give decent medical care to them. But is it just and desirable to do so?

Inter-generational Justice

Generally speaking, unless one subscribes to extreme individualism, there is a presumption that, to maintain the fabric of a society, there should be a just distribution of resources across the generations of a society. But inter-generational justice is usually rough justice. For instance, as we know, parents often make sacrifices so that their children will have better lives. More generally, a society’s stock of knowledge, inventions, tools and the like is passed to later generations providing them with resources and wealth that earlier generations did not have. So the justice issue is not a matter of treating each generation equally. It is a matter of treating each generation equitably, that is, fairly compared to other generations and according to the circumstances.

It has been said that justice consists in treating equals equally and unequals unequally. It is not always wrong to discriminate, in the sense of to distinguish and treat differently. To take a trite example, it is not wrong to refuse prostate specific antigen tests to women, or to refuse ovarian cancer tests to men. Conditions and circumstances alter cases. The issue before us is whether it would be inequitable to discriminate adversely against persons on the basis of age per se. Before pursuing this question further there is another issue that need to be addressed.

Age versus Aging

We sometimes see an obituary stating that so-and-so “died of old age.” No one ever dies of old age. If you will permit a philosopher to indulge in a little metaphysics, time per se has no efficacy. Events occur in time and processes endure through time. It is events and processes that are causes and effects; time itself does nothing. Hence chronological age, in and of itself, has no effect on death and dying.

What is true is that there is a normal aging process—to avoid confusion, let’s call it “senescence”—a process that takes place during one’s lifespan. Senescence is a decline in bodily functions: immunological responses, metabolic efficiency, tissue regeneration and the like. There are average rates of such decline, but there are many individual differences, some genetic and some circumstantial. So to die of “old age” is simply to die when and because the process of senescence has run its course.

What is also true is that there is some correlation between chronological age and stages of senescence. For example, it is estimated that 50% of those 85 years of age and over will have some degree of dementia. However, some people develop dementia in their fifties because of early-onset Alzheimer’s, some will not develop it until well into their nineties, and many long-lived will never develop it at all.

The distinction between age and aging and the limited correlation between the two is the second of the reasons—the first being the alleged scarcity of resources that I have rejected—why I am opposed to age-based rationing of medical resources. To be fair, we should treat people because of their disease or disorder and the feasibility of doing so, not because of their chronological age.

Values: Benefits/Disbenefits

We spend money on health care to achieve benefits. Often the intended benefit is an increase in expected longevity, an increase in years of life over what would be expected without the medical intervention. The oncologist says to her patient, “If you take this chemotherapy, you will extend your life by three months.” This is only anecdotal evidence, of course, but many people I have known have replied to this sort of statement with, “You are offering me another three months of misery. What counts for me is not the quantity of time I have left but its quality. It is not the years in my life but the life in my years that counts for me. I’ll forego the treatment.”

This idea of the quality of life has been embodied by economists and others in the concept of the QALY, the Quality Adjusted Life Year. A year in full health is given a value of one QALY. But, for example, you may think that a year suffering from the grinding pain of severe arthritis is worth only half a QALY. Similarly, QALY values can be assigned by individuals to other forms of suffering and disability. Indeed, surveys can be conducted to find the average values a population assigns to various forms of less than optimal health. Then these values can be used in cost/benefit studies of various medical interventions. Thus a surgical procedure costing $100,000 may, on average, prolong life by two chronological years, but measured in QALY’s the benefit may be only one QALY. Such studies might then be used to inform guidelines and best practices for a medical care system, and in decisions about the allocation of resources.

Frankly, I am sceptical of such schemes, which often involve fallacies of misplaced precision. People are often being asked to make value judgments about situations of which they may have had no experience. There may be positive qualities in a person’s life, or life work they still want to accomplish, that are being neglected in the focus on the negative qualities. What may be considerable differences in individual judgments are blurred into averages that then are used to apply to individual cases. There may be an excessive focus on measures of central tendency—means or averages—and a neglect of measures of variance, such as standard deviations.

Although it is important to have guidelines and best practices resulting from evidence-based medicine, it is individuals that are being treated, so I think that there must always be left room for clinical judgments and individual values in their application.

Golubchuk Redux

This brings me back, finally, to poor Mr. Golubchuk. He died on life support before the Court of Queen’s Bench could make a final determination, so the matter in his case is moot. However, an editorial in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, in April 2008, drew a fair and reasonable conclusion about the case:

Ultimately, neither side in the Golubchuk case seems especially in the right. The hospital failed the family by not giving them a fair and impartial hearing, and the family failed society by using their religion to privilege their father over other needy patients (9).

In emergencies medical personnel often have to make important decisions on their own, using general triage guidelines and clinical judgment. Generally, decisions should be made jointly by the physician and patient or designated proxies. Good compassionate communication is of the essence. In cases of impasse, the Canadian Critical Care Society recommends "recourse to either mediation or adjudication" (Cited in 9).

Rights to Scarce Resources

Obviously there are sometimes local shortages of medical resources in Canada. Mr. Golubchuk’s physicians thought that this was so in their situation. In a large country like Canada, with 80% of the population living in urban areas, there will be problems servicing the remaining 20% scattered in small communities, especially in the north. So-called “Life Boat Ethical Dilemmas” can present difficult problems about who should die, but they are rare. As the lawyers wisely say, “Hard cases make bad law.” Hard cases should be treated as exceptions to the general rule, with which we have mainly been concerned. (In desperately poor countries hard cases may be very common, but in Canada this is not the case.) When hard cases do occur because of scarcity of resources, there arises the issue of who has a right to the resources that do exist.

Rights impose obligations on others. Freedom rights impose duties of omission on others; demand rights impose duties of commission. My freedom of speech imposes on others an obligation of non-interference. My demand right that you repay a debt imposes on you the obligation to pay me the money. The Golubchuks had the freedom right to move their father elsewhere and pay for his care. What was at issue was whether they had the demand right on the state and hospital to keep him alive and pay the cost of doing so. The hospital thought he did not have that right in the circumstances.

One source, then, of relative shortage of resources can be unreasonable demands. Should my hypochondria impose on the community the cost of giving me a full-body MIR every year to detect the slightest anomaly? Or the cost of life support when I am in a persistent vegetative state? Or cryogenic preservation on my death in the hope that science one day will permit my resurrection? There needs to be, and our Charter of Rights permits, “reasonable limitations” on our rights.

Finally, many of us suffer from urangst, a primal fear of death, something that perhaps was an underlying issue in the Golubchuk case. To deal with this perhaps civil society needs some thoughtful discussions of a modern form of ars moriendi, the art of dying well—perhaps in symposia such as this.

References

1. Golubchuk v. Salvation Army Grace General Hospital et al. Date: 20080213, Docket: CI 07-01-54664, (Winnipeg Centre), Cited as: 2008 MBQB 49.

2. John Hardwig. Is There a Duty to Die? Hastings Center Report 27, no.2 (1997): 34-42.

3. John Hardwig, Nat Hentoff, Dan Callahan, Larry Churchill, Felicia Cohen and Joanne Lynn. Is There a Duty to Die and Other Essays in Medical Ethics? New York: Routledge, 2000.

4. Christine Overall. Aging, Death, and Human Longevity: A Philosophical Inquiry. Berkley: University of California Press, 2003. (Overall objects to the duty to die, but from a perspective different from the one I offer.)

5. Health Canada Report, Canada’s Aging Population. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/seniors-aines/pubs/fed_paper/fedpager_e.pdf

6. National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975-2007. Canadian Institutes for Health Information. http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/dispPage.jsp?cw_page=AR_31_E

7. Canada's aging population: demographic time bomb or economic myth? http://www.cma.ca/multimedia/cma/Content/Images/Inside_cma/WhatV/

8. Raisa Deber, Bill Swan. Canada's health expenditures: Where do we really stand internationally? Can Med Assoc J. 1999; 160: 1730-34.

9. Amir Attaran, Paul C. Hébert, Matthew B. Standbrook. Editorial: Ending life with grace and agreement. Can Med Assoc J. 2008; 178: 1115-16.

How Genes Work: The New RNA Surprise

Neil A. Straus

This talk is part of a larger presentation entitled Biotechnology and the RNA Paradigm Shift, that I was invited to present last month by the California Applied Biotechnology Center.

I will frame this talk with two quotations that succinctly encapsulate the reason why there was a RNA surprise in the very highly developed field of molecular genetics.

First, Sydney Brenner, scientist and Nobel Laureate said: “Progress in science depends on new techniques, new discoveries and new ideas, probably in that order.” I believe that this accurately describes how science moves forward. For example, because the compound microscope was invented, we were able to see cells, the building blocks of life. Without that technology, biology might still be Aristotelian.

Second, the economist John Maynard Keynes said: “The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping the old ones, which ramify… into every corner of our minds.” This explains why there was a RNA surprise. Old ideas prevented mainstream science from seeing the important roles that RNA plays in gene regulation and cellular biochemistry, despite the presence of overwhelming evidence pointing in that direction.

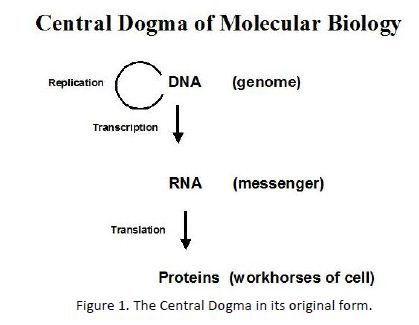

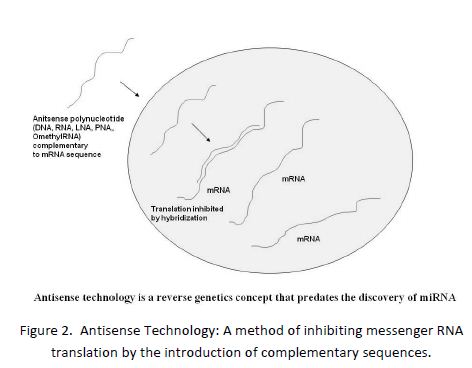

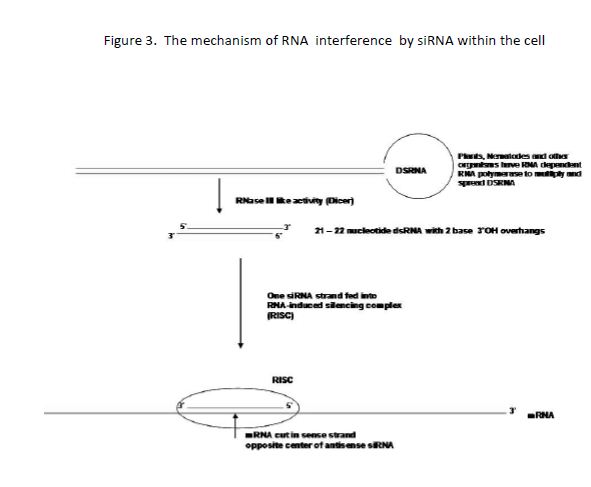

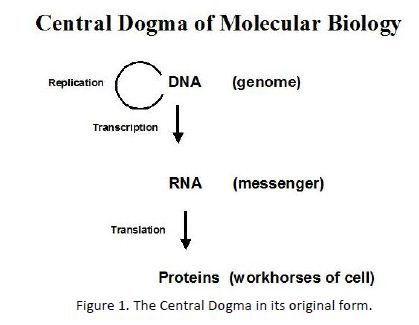

In this case, it was more than a bunch of old ideas suppressing scientific thought. It was the Central Dogma of Molecular Biology, a scientific tenet framed by one of the greatest scientists in molecular biology, Francis Crick (Figure 1). Evidently, he chose the word “dogma” because at that time he believed in the fundamental, universal truth of the statement.

The Central Dogma fixed the idea in everyones mind that RNA was simply an intermediate molecule of transcribed genetic information preserved in DNA. This information was then translated into proteins that performed all the remaining important functions of life, like cellular architecture, cellular metabolism and gene regulation. Inherent in this dogma was the assumption that if we could sequence all the DNA of the human genome and then translate this information into all the possible proteins, we would know everything about the molecular nature of our existence.

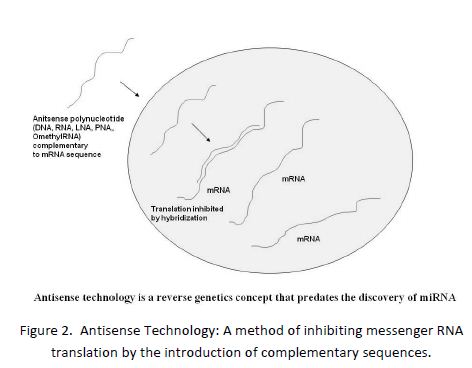

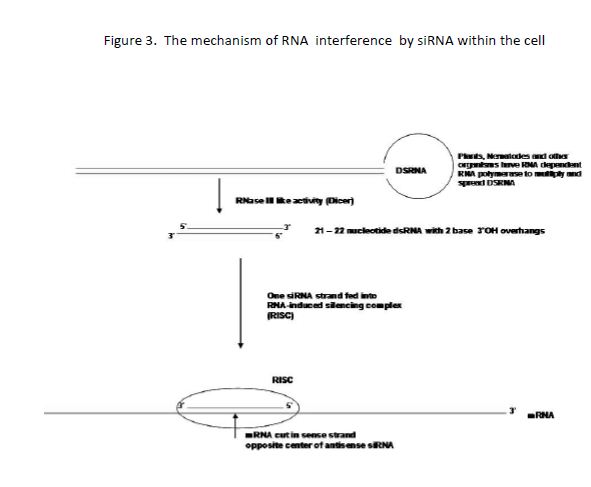

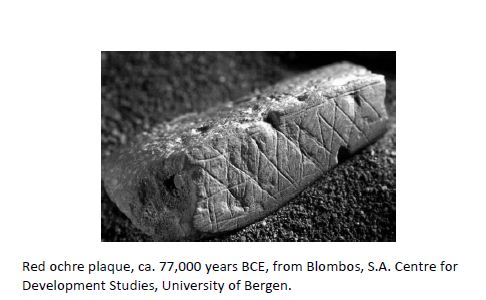

As Y2K approached we had the technology to do just that. The methods for sequencing DNA had been developed, and in 1998 Applied Biosystems built an automatic DNA sequencer, the ABI Prism 3730, that was capable of sequencing a million nucleotides a day. This meant that six thousand 3730s would be able to sequence the equivalent of both strands of the entire human genome in a single day. The race was on and the sequencing of the human genome was completed by the millennium. The two journals, Nature and Science, each published annotated versions of the complete human genome in their February 2001 issues. According to the Central Dogma, the real mystery of life should have been solved there and then. Only the exposition remained. Well not quite. The scientific world began to realize that it just had a lot more sequences of potential genes to work on. It was a case of the more you know, the more there is to know. But something else was happening to catch everyones attention.